Doing ethnography with politicians and activists in Texas

A conversation between Nicholas Sarra and Emma Crewe

In January 2023 Emma Crewe, an anthropologist from London, visited the Texas State Legislature in Austin, Texas, to research the 88th session as part of a broader study of the relationship between politicians and people in six countries (funded by the European Research Council). Artist ethnographer Nicholas Sarra joined her towards the end of the session in May 2023. (All images are by Nicholas Sarra).

Emma:

So how did you find yourself coming to Texas?

Nick:

I worked with you previously on Westminster select committees and in constituencies in the UK and I felt we’d begun to develop a way of working together, and of course we work together in the context of the Doctor of Management programme at the University of Hertfordshire. So, when I heard you were going to Texas, I thought it might be an opportunity to develop emergent ideas about how we might be able to expand ethnographic enquiry through the use of paintings and photographs. I had this idea that it might be useful to work with the detritus that people leave behind, the rubbish that people discard, the stuff that people walk by, that nonetheless speaks to the cultural expression of the institution that you know. So, we began to talk about that.

Emma:

Why would rubbish reveal something?

Nick:

It’s not necessarily the case it would reveal anything but I think for me it’s the equivalent of the public conversation and the private conversation or the front room, and then the backroom, that could be acknowledged. There’s also something interesting and revealing about what happens in corridors and private spaces, bedrooms, restaurants, that is not apparent in the formal structure of institutional life. Maybe those interactions can sometimes leave traces that help us to think about wider aspects in rather unknown ways. I had been previously engaged in making collages. The things of ordinary life that people might discard tell us something about the cultures in which people are involved.

Emma:

I think they can be both interesting and revealing.

Nick:

We could have a look at the rubbish of the 18th century, and sometimes it survived enough that we might get an opportunity to do that. It has an interest to us that we don’t always have in contemporary rubbish artefacts because we’re still too involved with them and to us they are still rubbish. So, I wanted to try and be like a time traveller, looking back and trying to see something about their expression. In the paintings I thought I might try and construct a feeling of archaeology in that they would also be composed of layers of stuff. There may be layers that are invisible but nonetheless are influential on our habitus, on how we might perceive things.

Emma:

I think one of the things that’s hard about trying to convey what politics is really like for people as everyday work, is that there’s continual movement, isn’t there? If you take a snapshot, or if you try and write about it in 1 output, it doesn’t already tell you enough. It occurs to me that one of the things that’s interesting about rubbish is that it is temporal. What might be rubbish now, only a week before it might have been an incredibly important piece of paper.

Nick:

That’s right; that it was expressing some political intent, some message to somebody else to try and persuade them, or threaten them, into doing something that you want. And then things move on and then that might become a trivial piece or it might actually be something really secret because it reveals some deal that was done that then needs to be destroyed. I was immediately in touch with how much it looks like an espionage activity.

It was funny when we went into the library, wasn’t it? We said to them we want to create something that conveys the excitement of politics and we’d like some rubbish and their eyes did widen in surprise a little bit, I would say initially. But they did seem to understand what it was we were doing. Over the next few days we had a number of conversations about this work and eventually a staffer gave us a whole file of rubbish.

I’ve become quite interested in the temporality of inquiry. It is a process: there’s something that is possible at the beginning and then some things become more possible as you engage in the inquiry.

Emma:

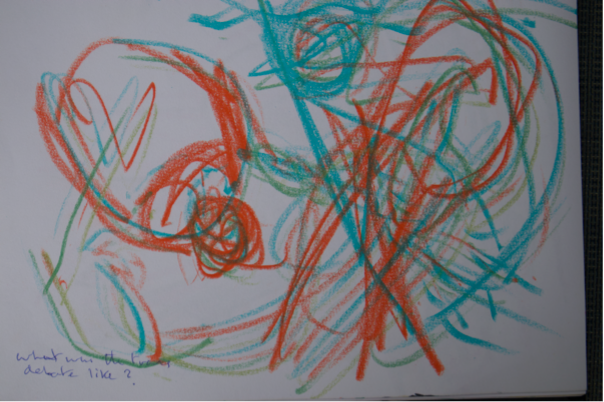

So, what was it like when you were painting the House of Representatives in the Texas State Legislature, while watching one of the most important debates of the whole session – the one about banning medical treatment for trans children?

Nick:

I found it was quite conflictual in a way. I was detached, on the one hand, because I was trying to paint about something and trying to respond to something. I think that puts you into a particular kind of attitude or particular kind of space in relation to what you’re doing, in which there is some degree of detachment, but at the same time I was very affected by the presence of numerous state troopers. The tension of the bodies around me. The tension of the debate. The looks the people were giving each other from both sides. I experienced some kind of turbulence within myself with the result that I was feeling, ‘Whose side shall I take? Who should I be with?’ That was the imagined pressure – that I was being invited to go into a particular position.

It was part of the process I’ve been involved in with you – going around talking to people, getting into conversations, and I experienced that kind of invitation. If I was talking to trans people, I was asked to be empathetic to their cause and to understand their position and feeling, like I was being sounded out as to whether I was supportive of their cause. And exactly the same thing would happen if I sat down and talked to people in red T-shirts that said Save Texas Kids on them. I would feel the same kind of pressure, which produced in me a feeling that I had to do quite a lot of emotional work not to disclose everything about a position and to sustain the relationship of inquiry.

Emma:

I remember being really interested in this question of impartiality and inclusion and making sure that in whatever way we communicate about what we experienced, everyone gets a say or is shown in a painting, for example. I remember thinking with some worry, “Are you going to make sure that all the colours that are important in this debate are present?” There was a huge symbolism to the colours. Obviously, the people who were for the bill were wearing red T-shirts and then the people who were against the bill were wearing pale pink, pale blue and pale purple to indicate that they were sympathetic to trans people and their families. I remember thinking, we have all these colours and in the same way that politicians have to grapple with the impossibility of representing thousands and thousands of their constituencies, I thought, “How on earth are you going to represent these people in a painting?”; this extraordinary diversity because although there were two sides, even within the sides, there were many, many sides.

Nick:

I didn’t want to be that concrete about it. I didn’t want to be too figurative about it. I didn’t want to collapse into a position of trying to represent something, and perhaps that was because I didn’t want my attitudinal disposition to be too apparent. But I think I also wanted the freedom to find out something else. I didn’t want to predetermine the outcome of what might arise from any images that I might produce and wanted to explore something without any, or without too much, constraint.

I think we’re both aware of the importance of trying to understand the plurality of perspectives in the situation and inquiry. I was consciously trying to attend to it, as I think you were as well. If we speak to people with one persuasion, then we also want to speak to people of another persuasion.

Emma:

Something you drew attention to during our inquiry was the extraordinary similarities between the polarised perspectives; how did you do that?

Nick:

The polarisation can mirror each other. The ‘wokeness’ of the right, for example. The GoP perceive problems in the Democrats, and they in turn can perceive the same difficulties in the GoP, but they find their own versions, such as wokeness in both or the difficulties around the marginalisation of minorities. It is not so apparent to the Democrats that they can marginalise people on the right as much as the other way around, for example during that debate on trans.

Emma:

It was during that debate that a new rule was introduced so that there was no photography in the Chamber. I liked it when the security guard looked down at you and said, “Ohh, you seemed to be one step ahead”, as he watched you paint him.

Nick:

That was quite an interesting little subversion of the rule.

Going back to what you were saying about the wider themes that were affecting the political parties, watching the debates raised all kinds of puzzles that I’d been grappling with for some months. The debate about trans was so fraught that it seemed to be about much more than just that debate. And I think that’s partly why I remember that we thought we better go and watch it.

Emma:

We also took our inquiry outside the legislature, which is of course connected to the whole of Texan society, partly through this claim that politicians represent their districts, which collectively covers the whole state. But also because there’s endless engagement between Representatives and people from outside. In Texas more than any Parliament I’ve seen people have opportunities to try and influence lawmakers, whether it is the lobbyists, activists or people from their constituencies. We talked to some of these people outside the legislature in and around Austin. I had already done this over some months in South, East and West Texas – as far as El Paso. In some disciplines that’s seen as contextual or icing or extra but actually, I think it became really central to our inquiry.

I wondered whether painting some of the encounters that we observed or got involved with outside the legislature played any part in wrestling with our puzzles? For example, I’m interested in that painting that you did in the Mega Church. Did painting the service affect your experience of it?

Nick:

It was quite tricky, because it was dark. It was noisy. It was crowded. It was very exciting because the whole place was buzzing. On entering the Church I found myself caught up in the emotionality of the experience. I even felt quite cheerful because of the strength of feeling in the room. All of that intensity and response made me suspicious of myself. I’m a bit worried when I start feel caught up in something like that.

The painting helped me to ground myself and find myself in that experience – it helped me to gain some detachment from it, whilst at the same time being involved in it. And it gave me a sort of valid thing to do. I wasn’t about to start praising god. Although when people were expostulating, I did let out a noise. But what I’m trying to draw attention to is that the painting experience grounded me in my sense of being able to think in that situation.

Emma:

There was another painting you did in a courthouse, in a nearby small town, and I was interested in that one because it was more figurative than all the other ones. The people were very discernible as people sitting at a table. You painted the room with lots of shapes created by the panels and the windows that were all clearly identifiable and I wondered why you got drawn towards more figurative painting in that one, whereas other paintings you’ve done are more mysterious?

Nick:

It might be related to the context – the feeling of control in the situation that I was in. There was something very kind of concrete and serious rooted in the environment that I was in. It was difficult to do anything else other than express myself in a more figurative way.

When I was in the Mega Church, there was a massive amount of movement going on. The legislature is quite a dynamic situation too. I mean I know there are times when it’s quite static but at other times people are moving around. I wanted to sort of respond to that kind of feeling of mystery and movement because I didn’t know really what was going on. I could speculate about the sort of things that were going on. You could help me to understand some of things that were happening in terms of responses to voting and amendments or the little cabals that had to congregate to sort something out, or when the Representatives were doing something in the moment that required a movement in the environment.

Emma:

On a point of order, for example?

Nick:

Yes, but to me it was actually inherently mysterious. Like being in a kind of church, where you don’t understand the ritual or understand anything that’s going on, but you know the movement of bodies is incredibly important – it reveals a lot.

Emma:

Yes, it reveals who is important at what point in a decision-making process. So, for example, in the Texas House as a lawmaker sitting or standing on the floor of the House, you can move around, you can go and talk to your potential ally or your opponent, and try to persuade them of something. Or you could even get on your phone, to talk to your staff or a lobbyist, for example. And then when there’s a vote, you need to rush back and go and physically press the button on your desk, unless your desk-mate will do it for you. But also, if there is a point of order and the Speaker announces it, then you all go and huddle around the Parliamentarian and explain your points of view to get it settled. They communicate the result to the Speaker and then the Speaker announces it to the whole House. This is all completely different from the rituals in the House of Commons. It’s very different between the Senate and the House in the Texas Legislature as well, partly affected by the size as the Texas Senate is only 31 people, whereas the House of Representatives is 150.

Nick:

In the House I think I came to focus on the relationship between the front mic and the back mic.

Emma:

That is really interesting again because if you think of it visually, it’s as if the individuals are having a debate – a bilateral debate between two people, as if their political party was in the background. In fact, they don’t even sit at desks in the Chamber grouped as political parties, unlike most legislatures, which you can only understand fully when you look at it visually. As you say, the front mic / back mic action is a really important process within Texas where two people are debating and they’re standing on their own, but often with supporters behind them. There’s a wonderful picture that you’ve drawn of two individuals thrashing out the arguments with the crowd around them listening, and you couldn’t easily explain that situation with words on their own. I think you really catch something in that painting.

I wanted to ask you about methodology. It felt to me as if when you were developing your methodology, painting and drawing had a different emphasis each. You seemed to get more collaborative with the people who you were drawing. Why did you do that? And could you say anything about what was going on there?

Nick:

At the beginning of the process, I think I was finding my way like one might do in any sort of approach to a relationship. It takes time. You have to try and judge what’s at stake. And you have to develop a kind of feel for what’s acceptable and what’s unacceptable.

When I first started, I didn’t have a clear idea of what would be upsetting or what would be difficult, but I knew that I was in a sensitive environment in which there would be a lot at stake for people. I sensed that at every turn. Whatever one did might be consequential: how one used language, how one used one’s body, how one appeared. And inevitably, one might make errors. So, I wanted to feel my way into it gradually because I didn’t understand and hadn’t been sufficiently inducted into how one should behave.

As I went on in the journey, I developed more confidence in who could be approached and when and how they could be approached and what I might risk. Then I started to develop more of an idea that they could also be involved in my own process of inquiry. Eventually I managed to get to a place where I was actively involving people.

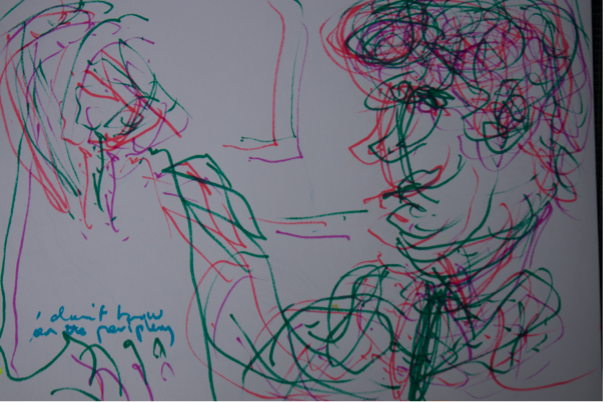

Then, we reached the place where we met up with an intern and you were interviewing him, asking him a number of questions and inquiring into his experience to try to understand the kinds of things that were important to him in his work and how he collaborated with allies. Whilst you were doing that, and I was witnessing you both, to his delight I think, I drew you interacting very rapidly and with multiple pens, without thinking too much about what was coming out. I wanted to get an image that later I could ask him to relate to and that’s what we did.

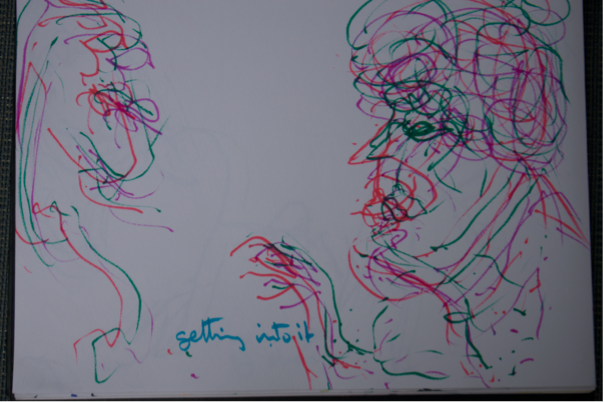

So, a conversation was generated around four or five images of him and you talking, by inviting him to think of the images as a temporal process and to respond to the images in terms of phases of the conversation. I asked him talk to us about what he remembered about these phases and what the image evoked for him about these phases and to give a title to the images. It seemed galvanising in terms of what he came up with but it took time. He started off saying, “I don’t know.” Then he said, “on the periphery”.

So, we developed the title of that particular image into the next one, “I don’t know” and “on the periphery”, which seems to me to encapsulate something of our experience at the beginning of a conversation, which in fact mirrored my own experience of joining you in your work in the legislature. Because he was at that stage trying to work out what was going on, who we were, whether we were trustworthy accomplices in this endeavour, and whether there was something plausible happening from his point of view.

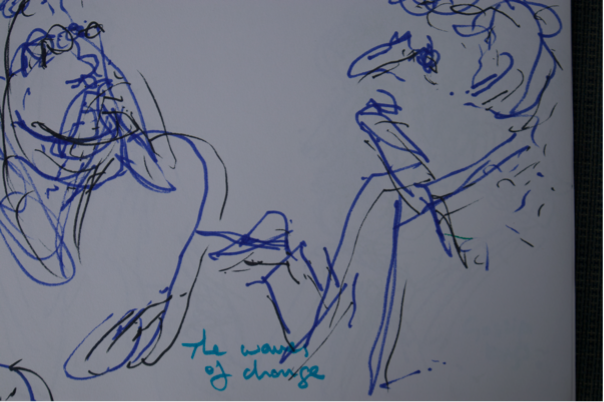

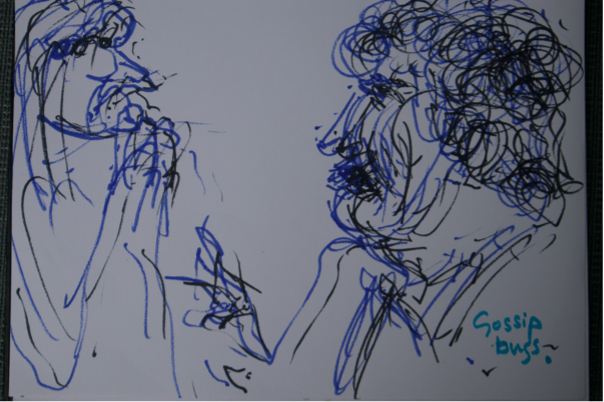

The second image he called, “getting into it”, then he called the next image, “the waves of change” and the final one, “gossip bugs”. He talked about how the pictures helped him to recalls bits of the conversation.

What’s important to people are emerging power dynamics, revealing what’s at stake in a more transparent way. We encouraged and reassured him but allowed him to take the lead in making sense of his experience of the conversation. I felt at this point we were really into some meaningful collaborative inquiry.

Emma:

Before that encounter I recall that we had started to struggle in our engagement with differences in how we perceive things and how we might sort of use those differences.

Nick:

Yes, I found myself at one point trying to develop some ideas about aesthetics and the significance of ritual in them and you felt excluded. I think at that point I’d lost you, but you were able to call it and asked me what was going on and then to talk about the gender aspects of men doing this sort of thing and how irritating it was. It made me think about how it created a little rupture in that moment that enabled us to find our way back into working collaboratively. Probably if we hadn’t managed to kind of face our own differences and call each other back into a collaborative relationship, when inadvertently we might both have stepped outside of it to our own respective disciplines and needs and so on and so forth, we might not have got to the point where we were able to do that kind of work with the intern.

Emma:

I recognise that something important happened in that rupture, and I think another way of putting it is that lots of different processes were all ongoing at the same time. It feels almost quite impoverished to try and draw attention to only a few, but we can’t talk about everything. I think there was a bit of a power struggle going on which arose out of the fact we’ve been trained differently. You’ve been trained in art history, in art therapy, in group analysis, in being a psychotherapist and I’ve been trained in anthropology. At the same time, we both share an interest in what actually goes on between people in organisations. So actually, despite the different training, we’ve got very strong interests in common in trying to develop ideas about what happens between people, which is both generalizable, but also arises out of that specific situation that we’re gazing at.

Nick:

I think there’s quite a lot of give and take most of the time and we allow the other person’s idea to lead when it feels right.

Emma:

You’ve been extremely respectful of the fact that I’ve been here for a while, and I’ve made these relationships, which is an important part of collaboration. But there was a moment, as you say, when I wasn’t quite sure what you were doing, where I wasn’t an equal player or something like that. I had a slightly paranoid moment of thinking you were going off in a direction that wasn’t intelligible to me. I think it’s easy to idealise collaboration as if it’s always harmonious.

Nick:

I think by its very nature collaboration implies an encounter with difference because otherwise you’ll just talking to yourself. At worst, one person’s following the other. But actually, when collaboration gets really exciting is when there’s a genuinely mutual possibility of creativity.

Emma:

Two people bouncing off each other sort of thing. It’s quite tiring, isn’t it? But if you have no conflict, it may mean what you’re doing is not that interesting. It’s important that the conflict doesn’t tip over into avoidance. So, what was the difference about I wonder?

There could have been elements of conflicts about the way we have related to the trans issues.

Nick:

My experience has been primarily as a clinician within mental health. You were in one position and I was in another. And within the context we were in, those positions could be potentially quite polarised and difficult to talk across that. There was one particular situation where we were trying to locate where the trans activists were because we were anticipating a demo. We couldn’t find them. As we were surrounded by people in red T-shirts saying Save Texas Kids I asked, “why don’t we go and ask one of the anti trans activists – they’re bound to know”. You went very pale and your jaw went very tight. And I knew that was something that you did not want to do at that particular moment. But somehow we managed to help each other into a situation where we ended up talking to a senior Republican politician. I think out of that engagement something became possible through our collaboration that would not otherwise have been possible.

Emma:

We helped each other when out of our comfort zones.